Embracing Assessment in a Students' Legal Assistance Context

Main Content

Published June 2018

Abstract

Assessment of Student Legal Assistance programs is challenging due to the highly confidential nature of the work. Attorneys are bound to confidentiality professionally and can lose their license to practice if violated. This article provides practical solutions to assessing highly confidential units and relates assessment to legal training concepts. The examples of assessment techniques and data provided here are from a Student Legal Assistance program at a large Midwestern institution of higher education.

Contributors

- Thomas E. Betz, Directing Attorney, Student Legal Service

- Belinda De La Rosa, Director of Assessment, Office of the Dean of Students

- Jane M. Williams, Associate Professor, Library Administration, Foreign Collections and International Law Librarian

Special thanks to Beckee Backman for her editorial assistance.

Report

Midwestern U is a large highly selective and research intensive institution with a student population of over 40,000. The recommendations and examples presented here are the result of a very successful collaboration between a Director of the Student Legal Assistance program and a Director of Assessment for the unit the program reports to. Since 2012 this Student Legal Assistance program has embraced assessment to inform their practice through the development of a series of surveys. All of the examples presented here are from various surveys administered during the 2014-15 academic year. The primary goal of this article is to demonstrate that there are assessment methodologies that can be used in highly confidential units which can identify best practices and continuous improvement.

There are at least 98 Student Legal Assistance programs at U.S. Colleges and Universities in 38 states. (Mroz, 2015). They have various titles such as Student Legal Service, Legal Assistance for Students, and Students’ Legal Assistance. The term “Students’ Legal Assistance” [SLA] will be used for consistency in this article. Program services vary. Some programs provide a panoply of services including court representation, consultation, and preventive legal education while others are consultation and referral only offices. (Kuder & Walker, 1983) (Mroz, 2015). Since these programs provide direct services to students, most report to a unit within the Division of Student Affairs.

Many programs are members of the National Legal Aid and Defender Association Student Legal Services Section. (National Legal Aid and Defender Association Student Legal Services Section [NLADA], 2016). Nearly all have an active role in providing preventive legal education as part of their essential mission. The various programs are usually a part of Student Services or Student Affairs. SLA programs are expected to engage in assessment which addresses the goals and objectives of the institution and in particular Student Affairs strategic goals. SLA offices overwhelmingly retain one or more part–time or full- time licensed attorneys. The key for SLA attorneys is to translate the language of higher education assessment into the familiar language of law and lawyers so that it makes sense to them as legal practitioners. Once this is done, the SLA attorney can adopt the generally accepted language of assessment.

Most attorneys in SLA offices see themselves first and foremost as attorneys, whether they are providing advice through consultation or service through representation, litigation or trial advocacy. They are trained as lawyers not as higher education experts in student development. Private attorneys rarely engage in assessment other than in determining client satisfaction in order to generate more clients and return business. Educational outcomes and retention impacts are not germane to the private practice of law. Similarly, public attorneys such as public defenders, prosecutors, and municipal counsel, do not generally engage in assessment. All three aspects of assessment, student satisfaction, educational outcomes, and student retention are at the crux of assessment in Student Affairs and are equally vital in the context of SLA. As assessment has become more common in Student Affairs, attorneys in SLA offices need to adapt and develop many tools that can demonstrate, with clear evidence, the profound impact on student lives that their services provide. There are many assessment strategies available to programs within the larger SLA community that staff attorneys may find beneficial to improve their services and processes.

Assessment in Student Affairs

For over a decade, leaders of higher educational institutions have embraced assessment as a primary strategy to justify the cost of a college education and provide transparency and accountability (Greenberg, 2007). In 2012, the White House released a new formula for awarding campus-based aid. The White House wanted to reward institutions that admit and graduate higher numbers of low-income students, document that students find employment upon graduation, and demonstrate “responsible tuition” policies (Blumenstyk, 2012). The national focus on the cost and outcomes of a college education has not gone unnoticed by Student Affairs professionals. Student Affairs has embraced assessment as a mechanism for documenting its contribution to student development and learning for decades. Upcraft and Schuh in Assessment in Student Affairs (1996) argue that it is a matter of survival for Student Affairs to document their contribution to student learning. Additionally, Bresciani, Gardner and Hickmott (2009) stipulate that assessment is important because it not only documents accountability but also assists with resources and funding, planning, policy and programming, and in creating a culture of continuous improvement. CAS Professional Standards for Higher Education (Council for the Advancement of Standards in Higher Education [CASHE], 2012) acknowledges the need for assessment and program evaluation to improve student and institutional outcomes. As a unit within Student Affairs, SLA programs should also engage in assessment to document student learning and satisfaction as well as to document the efficiency of office procedures.

How assessment can inform the practice of law.

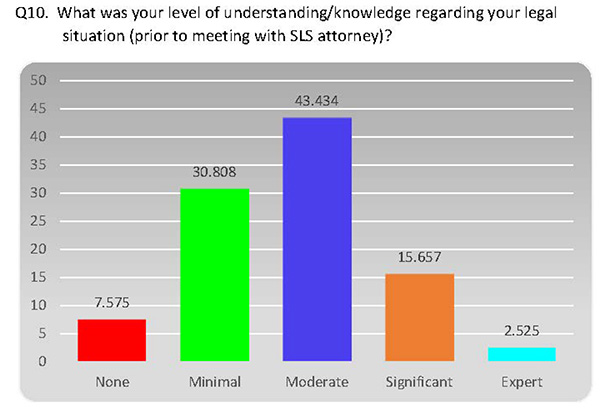

The first step for assessment in an SLA context is for the staff to understand the tremendous value that assessment will bring to the practice of law. There are numerous ways in which properly drafted assessment questions may inform the busy practice of law and demonstrate efficacy. One simplistic approach is to ask two questions on an assessment survey regarding level of knowledge before and after meeting with an SLA attorney. Figure 1 below illustrates knowledge level before meeting with an attorney. Clearly over a third of students had “minimal” or “no” understanding of their legal situation.

Q10. What was your level of understanding/knowledge regarding your legal situation (prior to meeting with SLS attorney)?

- None: 7.575

- Minimal: 30.808

- Moderate: 43.434

- Significant: 15.657

- Expert: 2.525

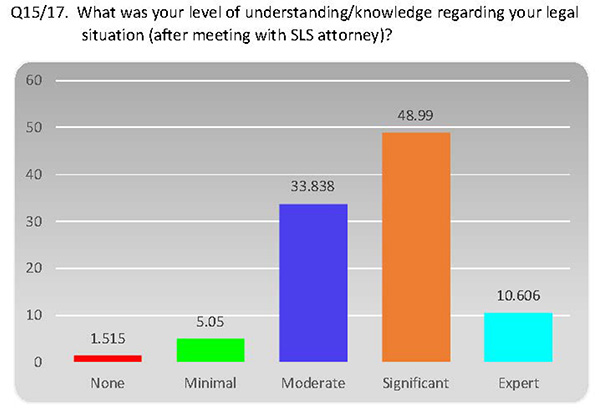

Figure 2 below indicates that this particular program is doing a great job of increasing students understanding by reducing the “none” and “minimal” responses to less than 7%. However, the percentage of students indicating moderate level of understanding was still relatively high at 34%. This is indicative of one of the problems most offices face which is that students constantly call or email to obtain follow-up or forgotten information. The results from Figure 2 led to the creation of a form on which students must write what the next step is. The client signs it and receives a copy. This new procedure will be assessed during the 2015-16 academic year. In lieu of, or in addition to a form, the attorney may engage in consciously prompting the student to answer, “What is the next step?” This simple assessment question and result can alter the interview process and reduce needless emails and telephone calls.

Q15/17. What was your level of understanding/knowledge regarding your legal situation (after meeting with SLS attorney)?

- None: 1.515

- Minimal: 5.05

- Moderate: 33.838

- Significant: 48.99

- Expert: 10.606

SLA attorneys certainly have a desire to improve their practice. It is important to know whether students have a greater understanding of their legal issue after consultation or representation. Figure 2 represents an opportunity to document efficacy. The absence of improvement should give rise to analysis of both results and how legal information and actions are being shared with student clients. These results can constructively inform the practice of law.

All programs maintain some form of a client intake system which, in combination with demographic information from surveys, can profoundly impact the practice of law so that preventive education efforts can be more intentional and focused. Survey and/or intake demographics may indicate disproportionate usage or need for services in selected areas of service such as housing/landlord issues, driving under the influence of alcohol, etc. This internal document audit is another assessment methodology that confidential units can incorporate into their overall practice for quality improvement. For example, knowing that housing/landlord issues are a major area of service can lead to collaborations with other units such a Tenant Union or University Housing. Internal document audits in combination with surveys may lead to identifying subpopulations such as student veterans or international students and programming that would provide preventative education. This use of intake or survey demographics will enhance fulfillment of the mission of SLA and Student Affairs to reach underserved student populations.

Students’ attorneys know more about assessment than they realize.

Law school, the bar exam and the practice of law, whether in private or public practice, involve evidence, rules of evidence, and evidentiary procedures. Decisions and consultations, as well as trial verdicts, must be based on evidence, not assumptions or suppositions. While science is inherently evidence-based, much of the practice of law is as well, in particular when attorneys use scientific evidence to make decisions, arguments, or inferences. It is important to strongly emphasize that evidence-based analysis and decision making should not be an alien concept for SLA attorneys. Assessment, at its root level, is the gathering of evidence through questions in order to determine whether certain things are taking place with clients such as satisfaction, learning outcomes and various permutations and domains of learning, and retention/persistence impact of services. One large Midwestern public institution has used surveys to assess satisfaction and learning outcomes of clients of their SLA program. This endeavor has been very successful and the unit has won recognition from its Division of Student Affairs for assessment excellence.

Surveys and client satisfaction.

The easiest questions to develop in an assessment instrument are those dealing with client satisfaction. It is very important for attorneys to know that the old adage, “You cannot please all of the people all of the time,” is doubly true in a law office context. Significant and consistent negative results should lead, however, to an examination of practices, behaviors, etc. The vast majority of student clients are likely to provide very positive feedback. The following are examples and results from questions asked at one Midwestern SLA program using a Likert scale (Strongly Agree [SA], Moderately Agree [MA], Neither Agree nor Disagree [NA/D], Moderately Disagree [MD], Strongly Disagree [SD]):

I felt I was treated with courtesy and respect by Students’ Legal Assistance staff.

- SA 85%

- MA 11.7%

- NA/D 3.3%

- MD 0%

- SD 0%

Staff members were approachable; I could discuss my legal issue freely.

- SA 83.3%

- MA 10%

- NA/D 3.3%

- MD 1.7%

- SD 1.7%

I would use Students’ Legal Assistance again if I had a qualifying legal problem.

- SA 80%

- MA 10%

- NA/D 5%

- MD 3.3%

- SD 1.7%

The staff afforded me adequate opportunity to participate in the handling of my case.

- SA 78.4%

- MA 8.3%

- NA/D 8.3%

- MD 0%

- SD 5%

There are obviously many different constructions of satisfaction questions; attorney specific and case outcome satisfaction in general, congruence of staff/client goals, and even questions about trust in the legal system may have profound impact on how clients perceive attorneys in general, as well as their individual attorney from an SLA program.

Learning/Educational Outcomes

It is widely acknowledged that much of the learning in higher education takes place outside of the traditional classroom. A significant array of research supports this viewpoint (Kuh, 1993). Student Affairs/Services, in general, and SLA, specifically, are key components of non-classroom learning which can include life skills, coping with crisis, time management, developing student resiliency and grit, and tolerance.

Several survey enquiries can be fashioned that test general as well as specific learning outcomes. Below are examples and responses to student learning outcomes using a Likert scale:

After consulting with Students’ Legal Assistance, I feel better equipped to handle similar situations in the future.

- SA 64.8%

- MA 16.7%

- NA/D 12.9%

- MD 1.9%

- SD 3.7%

As a result of my experience with Students’ Legal Assistance, I am more aware of resources available at the university.

- SA 68.5%

- MA 22.2%

- NA/D 5.6%

- MD 0%

- SD 3.7%

As a result of my experience in the legal process, and because of the way Students’ Legal Assistance operated, I have a better understanding of the options available to me including non-court options.

- SA 46.3%

- MA 20.4%

- NA/D 22.2%

- MD 7.4%

- SD 3.7%

Confidentiality in electronic surveys.

The mechanics of survey construction should not be daunting given the available examples in the SLA community. Attorneys are properly concerned with protecting client confidentiality as required by the canons of ethics. (Rule 1.6, Confidentiality of information, 2015). Electronic surveys can be developed that contain appropriate precatory language that does not violate confidentiality rules (see example below):

The procedures for administering this survey were developed to maintain your anonymity from any party and to maintain the anonymity of who responds to the survey. However, when you use a computer to respond to a survey, the IP address of the computer you use will be transmitted to the company hired to conduct and provide analysis of this survey. No one intends to use this information for any purpose: however, you may want to use a public terminal if you do not want your IP address to be logged by the vendor.

The surveys are sent out to all students who have used the SLA program, which is the legal cognate of a jury array. Those who actually answer could be considered the venire. The questions could be thought of as voir dire of the jury. Another helpful way for attorneys to think about assessment is in terms of their courtroom training in “direct and cross-examination” of witnesses: a series of written questions and follow-up questions that paint an evidentiary picture for the judge or fact finder, but in the case of assessment, for the fee committee and student services and the larger university community.

In Student Affairs, outreach is vital. Students need to know where to turn to for information and advocacy when an issue arises. Many units use outreach event surveys widely, and these can easily be obtained and modified for a SLA program. Outreach events generally are an aspect of preventive legal education where specific learning outcomes can be demonstrated by asking specific questions such as:

Please describe one new thing that you learned as a result of this educational program.

Questions can be more pointed with regard to specific topical content where answers may or may not demonstrate whether SLA objectives are being met and their relation to the strategic goals of the division of Student Affairs/Services. Qualitative analysis of these types of open-ended questions is an assessment technique that does not require extensive technical knowledge and may lead to the discovery of patterns of practices that are beneficial/efficient and areas that may need improvement.

Artifacts and Anecdotes; Hearsay to Lawyers

Web-based Surveys and outreach/preventive education questionnaires are not the only types of evidence that attorneys can use. Gathering and retaining thank-you notes, letters, etc., as artifacts of client satisfaction/dissatisfaction, can easily be done. While somewhat akin to anecdotal evidence, these notes may have greater reliability when unsolicited and submitted in written form. Attorneys trained in the rules of evidence tend to be very skeptical of this type of material; however, the information being gathered is not subject to the rules of evidence and is not being submitted to a court. It is useful for attorneys to think of the material as an exception to the hearsay rule but an exception that is not found in either the Federal Rules of Evidence or the Model Code of Evidence. One can think like a lawyer while treating artifacts, i.e., out of court assertions, as informative but not necessarily dispositive or legally admissible regarding any given issue. This will create more comfort for the attorney in using this type of information in the overall assessment process. Additionally audits of office documents can yield information regarding the types of students, cases, educational programs, or other services that can shape the planning for, resources necessary for, and delivery of services. The results of these audits can easily be put in a spreadsheet, and simple quantitative analysis can be conducted, such as averages, percentages, and/or correlations. Quantitative analysis lends itself easily to graphical representation of data which adds appeal to annual or other reports.

Focus Groups

Another assessment strategy that may be useful is focus groups [FG]. It is an efficient method to collect data from groups of individuals that share a common characteristic, such as receiving service from an SLA (Upcraft and Schuh, 1996). Groups of students can be interviewed at one time, and an experienced facilitator can generate more information than through one-on-one interviews. Groups of students can share common or unique experiences and verbally reflect during the conversation on items that they may not have realized until the conversation sparked it. Use of FG as an assessment technique can create significant ethical issues, which likely will prevent the use of this method (Rule 1.6, 2015).

The FG technique would require informed consent by the client to allow the breach of attorney-client confidentiality, which reveals client identity to a third party, and in turn potentially reveals confidential information amongst peers in the focus group. What is revealed in the FG will rarely be deemed to be legally protected. The Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act of 1974 (FERPA, 2016) has several exceptions regarding student privacy, while Rule 1.6 of the ABA Model Rules of Professional Conduct (2015) is far stricter in its exceptions; SLA attorneys are bound by both. For purposes of confidentiality and disclosure, the stricter ABA Rules of Professional Conduct are preserved by FERPA. For example, the University of Illinois Guidelines and Regulations for Implementation of the Family Educational Rights and Privacy (University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 1996) states, “Nothing in these Guidelines and Regulations shall be construed as authorizing or directing a violation of State law or as limiting individual privileges afforded by State law.” Case law similarly recognizes that attorney-client privilege is protected by FERPA. (State ex rel. Besser v. Ohio State University, 2000).

Attorney licensure is at stake in any consideration of the use of FGs of clients or former clients. While FGs present difficult issues as an assessment tool in the SLA context, most other methods remain viable. However, there is a possibility that the FGs as an assessment strategy could be used without disclosure of client identity or harmful information by SLA attorneys. Partnering with an assessment professional or faculty member who can conduct focus groups is an alternative method. An assessment professional can solicit the general student population and invite students who have utilized some service provided by the SLA office to a focus group. This voluntary self-disclosure can be confidential and only aggregate data should be reported. The assessment professional can develop the questions in collaboration with staff from the SLA office to ensure that the goals of the office or the division of Student Affairs/Services are met. However, only the assessment professional would conduct the focus groups and analyze the data. The aggregate data can then be reported back to the SLA office for the improvement of services/processes or documentation of student learning outcomes.

As a result of research atrocities such as Nazi human experimentation in Germany and the Tuskegee Experiment in the United States, the protection of human subjects became paramount. In 1974, the National Research Act established the National Commission for the Protection of Human Subject of Biomedical and Behavioral Research. The primary mission of this commission was to develop ethical principles and guidelines for the conduct of research on human subjects. These ethical principles are based on respect for persons, beneficence, and justice. Beneficence refers to ensuring that human subjects do not suffer any undue risk or harm as a result of participating in a study. Risk can include the disclosure of personal information regarding the use of SLA services. The protections established by the commission have led to the establishment of Institutional Review Boards across the world. These boards ensure that the guidelines established by the commission are adhered to by researchers in their institutions (Belmont Report, 1979). Institutional Review Board approval should be sought to provide an additional level of scrutiny to ensure there is no disclosure of potentially harmful information.

Retention/student persistence.

This area of assessment may be the most critical for SLA programs. It can be very difficult to prove a direct correlation between provision of service and student retention using surveys. Surveys should not be the only tool although questions can be fashioned that can be indicative of strong retention/persistence impact. SLA programs should track cases where students avoided eviction, jail, etc. A student in jail for a minor offense is not in class and is likely to have difficulty completing class work. Students in crisis over an illegal or even a lawful eviction are very likely to have to miss class, which does not bode well for student success, at least on a temporary basis. SLA programs often prevent untoward impacts. The office should document these potentialities versus their successful ameliorations.

Assessment surveys can be a valuable tool where students will actually acknowledge the impact of SLA in allowing them to remain in school. Below are examples of questions and responses from a Midwestern institution:

Without legal help, I would have considered leaving school.

- SA 11.2%

- MA 7.4%

- NA/D 11.1%

- MD 7.4%

- SD 62.9%

The Services provided by Students’ Legal Assistance enhanced my ability to focus on my studies.

- SA 27.8%

- MA 18.5%

- NA/D 44.4%

- MD 5.6%

- SD 3.7%

The services allowed me to feel less stressed about my legal issue.

- SA 38.9%

- MA 31.5%

- NA/D 20.4%

- MD 5.5%

- SD 3.7%

The services provided by Students’ Legal Assistance restored and/or enhanced my sense of well-being.

- SA 25.9%

- MA 27.8%

- NA/D 37%

- MD 5.6%

- SD 3.7%

There are numerous ways to phrase retention questions. It must be kept in mind that “considered leaving school” is on-point regarding student persistence; however, social life, emotional well-being, family life, and stress questions may have equal impacts regarding this critical issue.

There are also other strategies for correlating retention by comparing graduation or persistence rates of students who use SLA services and a similar cohort that do not. Grade point averages are also often used as a predictor of persistence. Other assessment strategies that can inform student learning are pre- and post-tests with respect to an educational program. As mentioned earlier document audits, e.g., use of intake forms, can also provide valuable information.

Conclusion

Students’ Legal Assistance offices, as part of higher education, should be able to embrace assessment in a relatively painless manner and free from the fear of disbarment. It is important that staff attorneys recognize the cognates between the language of assessment and the language of law, in particular in the area of evidence. SLA programs should realize that staff attorneys have a foundational knowledge of assessment as a result of their training. They need to approach assessment from this perspective and learn a few techniques. Assistance from assessment consultants would also allow these programs to build an efficient assessment plan that will provide data for continuous program improvement. Most assessment techniques can be effectively and ethically used in the context of an SLA. Institutional Review Board approval adds an additional level of protection for students. The examples provided here can be adapted by any SLA program. Offices that embrace assessment will likely be able to demonstrate efficacy and improve delivery of services as well as demonstrate education and retention impacts for users of Students’ Legal Assistance program services.

References

- Belmont Report (1979, April 18). The Belmont Report: Ethical principles and guidelines for the protection of human subjects of research. Retrieved April 7, 2016, from www.hhs.gov/ohrp/humansubjects/guidance/belmont.html

- Blumenstyk, Goldie (2012, January 30). College officials welcome Obama’s focus on higher-education costs, but raise some concerns, Chronicle of Higher Education. Retrieved from chronicle.com/article/President-Puts-College-Costs/130503/

- Bresciani, Marilee J., Gardner, Megan Moor, and Hickmott, Jessica (2009). Demonstrating student success: A practical guide to outcomes-based assessment of learning and development in student affairs. Sterling, VA: Stylus Publishing.

- Council for the Advancement of Standards in Higher Education (2012). Assessment Standards. In CAS professional standards for higher education (8th Ed.), Washington D.C: Author.

- Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act of 1974 (FERPA), 20 U.S.C. §1232g. (2016). Retrieved from uscode.house.gov

- Greenberg, Dan, (2007, December 13). Accountability, transparency, and hogwash [Web log post]. Retrieved from chronicle.com/blogs/brainstorm/accountability-transparencyhogwash/5551

- Kuh, George D (1993, June 20). In their own words: What students learn outside the classroom, American Educational Research Journal, 30: 277-304. doi: 10.3102/00028312030002277

- Kuder, James and Walker, Margaret (1983). Legal services for students, 21 NASPA Journal 23-26. doi: 10.1080/00220973.1983.11071863

- Mroz, Kelly A (2015, January). Meeting the legal needs of college students, The Pennsylvania Lawyer.

- National Legal Aid and Defender Association Student Legal Service Section (2016). About Us. Retrieved from www.nlada-sls.org

- Rule 1.6, Confidentiality of information (2015). In American Bar Association, Center for Professional Responsibility, Model rules of professional conduct. Retrieved from: www.americanbar.org/groups/professional_responsibility/publications/

model_rules_of_professional_conduct/rule_1_6_confidentiality_of_information.html - State ex rel. Besser v. Ohio State University, 87 Ohio St. 3d 535, 2000 Ohio 475, 721 N.E.2d 1044 (2000).

- University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Guidelines and regulations for implementation of the family educational rights and privacy act (1996), Campus Administrative Manual, Section XII. Retrieved from cam.illinois.edu/x/x-6.htm

- Upcraft, M. Lee and Schuh, John H. (1996). Assessment in student affairs: A guide for practitioners. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Inc.